Virome Bytes: Prophages in Lactobacillus

Hi! I'm Ryan Moore, PhD bioinformatics data scientist, functional programming fan, and sports nerd. Contact me on LinkedIn!

I wanted to start a little column where I would take some new(ish) virome papers that I like, and talk a bit about them. Given that this is the first entry, I think it’s kind of funny that these two papers are not actually virome papers! While these studies aren’t looking at viromes per se, I see them as sort of “virome-adjacent”–papers that I think will still be of interest to virome researchers who work mainly with environmental or microbiome data sets.

Lysongenic phages are pretty interesting. When they infect their host, rather than lysing the cell directly, they integrate into the genome. While snug inside the host genome, the prophage isn’t just along for the ride. Sometimes they can be a burden to their host. For example, there is a metabolic consequence for maintaining the extra genetic content (sometimes up to 16% of the total genome!!), and eventually prophages can activate and kill there host. On the other hand, prophages can provide superfection immuntiy (protection against similar phages) to their host, and can confer other advantages, such as beneficial virulence factors. However, there are only a couple of studies that look at the effect of prophages on host ecology actually conducted in the environment (see see here and here for two examples).

Prophages in Lactobacillus reuteri

With this in mind, Jee-Hwan Oh and colleagues published a really cool study in Applied and Environmental Microbiology called Prophages in Lactobacillus reuteri are associated with fitness trade-offs but can increase competitiveness in the gut ecosystem (Nov. 2019). In the study, the authors looked at prophages present in a set of phylogenetically diverse Lactobacillus reuteri strains. L. reuteri is a Gram-positive bacteria found in the guts of vertebrates and is often used as a model for studying gut symbionts and their hosts. One strain, L. reuteri 6475 (a human isolate) has some nice genome editing tools including a CRISPR-Cas genome editing system that make it a good strain to work with. This particular strain also has two biologically active prophage genomes that are induced in the GI tract.

The main points of this paper go something like this:

- They checked a bunch of L. reuteri genomes for prophages with PHASTER (a computational tool to predict prophage regions in sequenced genomes).

- They took a bunch of strains of L. reuteri, hit them with Mitomycin C, and then checked for prophage induction.

- They built and extensively tested a sweet experimental system around L. reuteri 6475, including a derivative lacking both phages, a sensitive host, single phage deletions, and more.

- They used this system to test some hypotheses about the affect of prophages on host fitness in the gut environment.

They used this system to show that prophages reduce the fitness of L. reuteri during gastrointestinal transit, and did some fancy work to show that phages were actually produced during GI transit in an SOS-dependent manner. Even though the propahges were found to reduce host fitness in the GI tract, the authors found that biologically active prophages are widely distributed among phylogenetically diverse strains of of L. reuteri.

If you stop to think about it, that’s a little weird. Why are all these L. reuteri strains, across multiple lineages, maintaining prophages over evolutionary time scale if the prophages are reducing their host’s fitness? The authors figured that production of phages by lysogenized L. reuteri strains may provide a competitive advantage by killing competitor strains. So they used their experimental system and did a whole bunch of competition experiments in germ-free mice. To make a long story short, the L. reuteri strains with the prophages beat out the strains without them. In other words, the prophage carrying L. reuteri strains had a competive advantage over the others in vivo, presumably because the non-lysogenized strains were susceptible to the phages produced by the lysogenized strains.

This competiteve advantage is one potential explanation for the widespread distribution of prophages found in gut bacteria. While the lysogenized L. reuteri strains outcompeted non-lysogenized strains susceptible to their phages, there was still a decrease in overall fitness of the lysogenized strains. Such fitness trade-offs (as mentioned in the title!) may help to explain the co-existance of closely related lysogenized and non-lysogenized strains.

Overall, a really cool study with some interesting results that I definitely encourge you to check out!

Citation: Oh, J.-H. et al. Prophages in Lactobacillus reuteri are associated with fitness trade-offs but can increase competitiveness in the gut ecosystem. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. AEM.01922-19 (2019). doi: 10.1128/AEM.01922-19.

Prophages in Lactobacillus brevis

Another recent study also looked at prophages of Lactobacillus: Biodiversity and Classification of Phages Infecting Lactobacillus brevis (publishd by Feyereisen and collegues in Fronteirs in Microbiology, Oct. 2019). Whereas the previous study focused on phages of Lactobacillus reuteri, this one focused on phages of Lactobacillus brevis. L. brevis is particularly well known for its ability to grow and survive in beer, leading to spoilage.

As we know, prophage induction will generally cause cell lysis and death, so learning more about prophages in an important beer-spoilage bacteria should be beneficial to the beer making industry. According to the authors, prophages could act as beneficial antimicrobial agents in beer fermentation, providing an alternative current practices. Additionally, few L. brevis phages have been characterized, so a study looking at the biodiversity of these phages is a welcome addition to the literature.

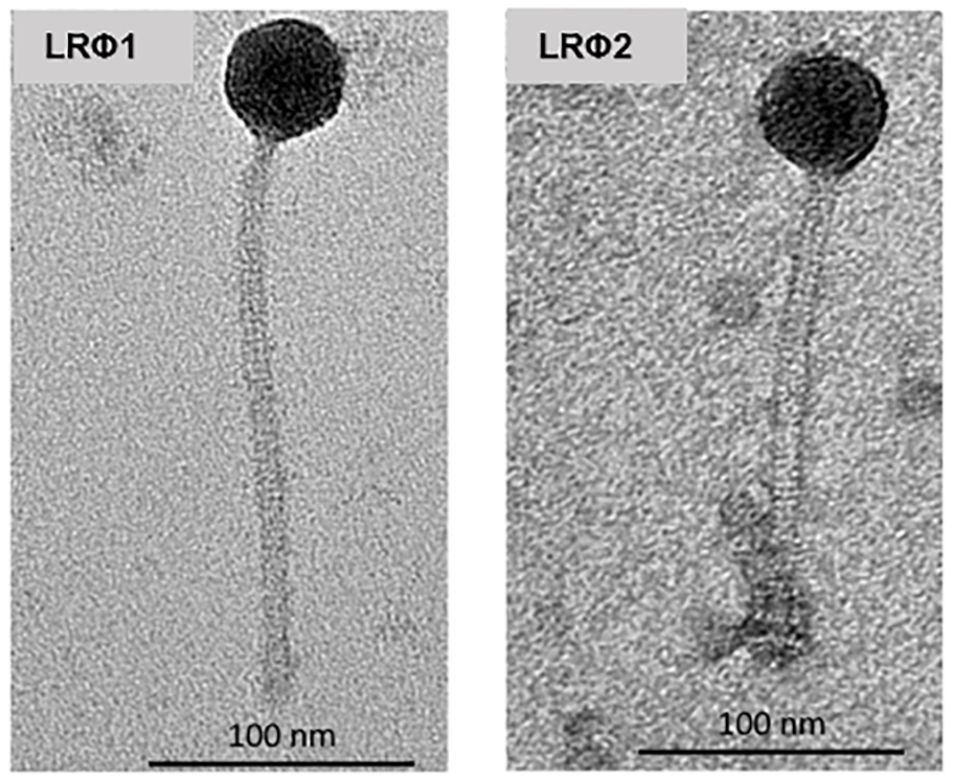

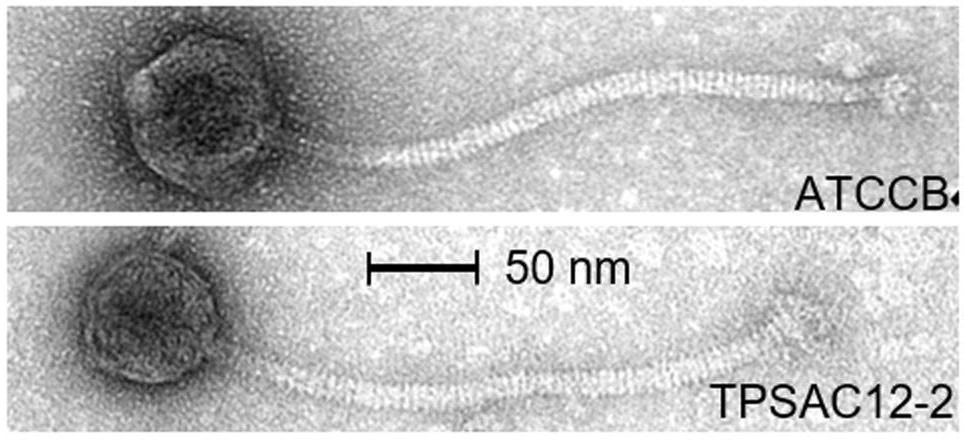

In the this study, the authors collected nineteen publically available L. brevis genome sequences from which they identified putative prophage sequences using a combination of PHASTER and manual annotation. Five of the strains were available for prophage induction trials. They also looked at the relatedness of the L. brevis phages and proposed a classification scheme for them based on virion morphology and genome sequence data (cool!).

Prophages were common in the tested genomes, with one of the genomes having four predicted prophage regions! Some of these were found to encode superinfection proteins, which could indicte that these prophages are boosting host fitness by confering resistance to infection by other phages.

The authors set up a classification scheme for L. brevis phages based on morphology, phylogeny, and genomic diversity, and provide a lot of interesting discussion about the defining charateristics of the five groups they defined. Overall, the L. brevis phages showed substantial diversity. Many of the identified prophages belong to the Myoviridae. This is unusual for prophages of Lactic acid bacteria like L. brevis, as generally members of the Siphoviridae are more typically seen (see Brüssow and Desiere, 2001, Casey et al., 2015, and Kelleher et al., 2018).

This is a nice paper to study if you are interested in looking at prophages in your favorite genomes or systems. They provide a pretty good model to follow for identifying, characterizing, and classifying phages and prophages from particular organisms. Check it out!

Citation: Feyereisen, M. et al. Biodiversity and Classification of Phages Infecting Lactobacillus brevis. Frontiers in Microbiology 10, 2396 (2019). doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02396.

If you enjoyed this post, consider sharing it on Twitter or LinkedIn and subscribing to the RSS feed! If you have questions or comments, you can find me on LinkedIn or send me an email directly.

← Go back